Minimum Support Price and Farm Bills 2020 have been in the news for quite some time now. In this blogpost let us understand what is Minimum Support Price and the recently introduced Farm Bills 2020.

Farm Bills 2020 and Minimum Support Price (MSP)

What is the Minimum Support Price (MSP)?

- Minimum Support Price (MSP) is a form of market intervention by the Government of India to insure agricultural producers against any sharp fall in farm prices.

- The minimum support prices are announced by the Government of India at the beginning of the sowing season for certain crops on the basis of the recommendations of the Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices (CACP).

- The government uses the MSP as a market intervention tool to incentivize production of a specific food crop which is in short supply.

- It also protects farmers from any sharp fall in the market price of a commodity.

- MSP is computed on the basis of the recommendations made by the Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices (CACP).

How does the CACP fix the MSP?

- It considers factors such as the cost of production, change in input prices, market price trends, demand and supply, and a reasonable margin for farmers.

- The Food Corporation of India, which is the nodal agency for procurement, along with State agencies, establishes purchase centres for procuring food grain under the price support scheme.

- The State government decides on the location of these centres with the aiming of maximising purchases.

Importance of MSP

- The share of agriculture in India’s GDP has fallen steadily from around 25 percent in the early part of the century to less than 17 percent now. But almost half of India’s population is dependent on agriculture for livelihood.

- Farming is a risky business with the farmer’s income depends on the vagaries of weather and pests, as well as local and international price trends.

- The MSP mechanism shields farmers to an extent, from such risks, by guaranteeing a floor price for their produce.

- MSP also ensures that the country’s agricultural output responds to the changing needs of its consumers.

- Higher MSP and rising farm income can augur well for companies that make consumer durable goods, automobiles or FMCG.

Besides, higher farm profits will encourage farmers to spend more on inputs, technology etc., which can have a positive rub off on companies in the Agri inputs and farm equipment space.

Current Scenario and latest changes/laws:

The Centre currently fixes MSPs for 23 farm commodities —

1. 7 kinds of cereal (paddy, wheat, maize, bajra, jowar, ragi and barley),

2. 5 pulses (chana, arhar/tur, urad, moong and masur),

3. 7 oilseeds (rapeseed-mustard, groundnut, soyabean, sunflower, sesamum, safflower and nigerseed) and

4. 4 commercial crops (cotton, sugarcane, copra and raw jute).

Farm Bills 2020

Recently, three Bills on agriculture reforms were passed:

1. The Farmers’ Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Bill, 2020

2. The Farmers (Empowerment and Protection) Agreement of Price Assurance and Farm Services Bill, 2020

3. The Essential Commodities (Amendment) Bill, 2020

What are the Three Bills?

- The Bills which aim to change the way agricultural produce is marketed, sold and stored across the country were initially issued in the form of ordinances in June. They were then passed by voice vote in both the Lok Sabha and the Rajya Sabha during the delayed monsoon session this month, despite vociferous Opposition protest.

- The Farmers’ Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Bill, 2020, allows farmers to sell their harvest outside the notified Agricultural Produce Market Committee (APMC) mandis without paying any State taxes or fees.

- The Farmers (Empowerment and Protection) Agreement on Price Assurance and Farm Services Bill, 2020, facilitates contract farming and direct marketing. The Essential Commodities (Amendment) Bill, 2020, deregulates the production, storage, movement and sale of several major foodstuffs, including cereals, pulses, edible oils and onion, except in the case of extraordinary circumstances.

- The government hopes the new laws will provide farmers with more choice, with competition leading to better prices, as well as ushering in a surge of private investment in agricultural marketing, processing and infrastructure.

- These reforms aim to accelerate growth in the sector through private sector investment in building infrastructure and supply chains for farm produce in national and global markets.

- They are intended to help small farmers who don’t have the means to either bargain for their produce to get a better price or invest in technology to improve the productivity of farms.

1. The Farmers’ Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Bill, 2020

- Aims at opening up agricultural sale and marketing outside the notified Agricultural Produce Market Committee (APMC) mandis for farmers.

- Removes barriers to inter-State trade

- Provides a framework for electronic trading of agricultural produce.

- It prohibits State governments from collecting market fee, cess or levy for trade outside the APMC markets.

2. The Farmers (Empowerment and Protection) Agreement of Price Assurance and Farm Services Bill, 2020

- Relates to contract farming, providing a framework on trade agreements for the sale and purchase of farm produce.

- The mutually agreed remunerative price framework envisaged in the legislation is touted as one that would protect and empower farmers.

- The written farming agreement, entered into prior to the production or rearing of any farm produce, lists the terms and conditions for supply, quality, grade, standards and price of farm produce and services.

- The price to be paid for the purchase is to be mentioned in the agreement.

- The method of determining such price, including guaranteed price and additional amount, will be provided in the agreement as annexures.

3. The Essential Commodities (Amendment) Bill, 2020:

- Removes cereals, pulses, oilseeds, edible oils, onion and potatoes from the list of essential commodities.

- The amendment will deregulate the production, storage, movement and distribution of these food commodities.

- The central government is allowed regulation of supply during war, famine, extraordinary price rise, and natural calamity while providing exemptions for exporters and processors at such times as well.

- The ordinance requires that imposition of any stock limit on agricultural produce must be based on price rise.

- A stock limit may be imposed only if there is a 100% increase in the retail price of horticultural produce; and a 50% increase in the retail price of non-perishable agricultural food items.

Will farmers get minimum support price?

- Most of the slogans at the farmers’ protests revolve around the need to protect MSPs, or minimum support prices, which they feel are threatened by the new laws. These are the pre-set rates at which the Central government purchases produce from farmers, regardless of market rates, and are declared for 23 crops at the beginning of each sowing season.

- However, the Centre only purchases paddy, wheat and select pulses in large quantities, and only 6% of farmers actually sell their crops at MSP rates, according to the 2015 Shanta Kumar Committee’s report using National Sample Survey data.

- None of the laws directly impinges upon the MSP regime. However, most government procurement centres in Punjab, Haryana and a few other states are located within the notified APMC mandis.

- Farmers fear that encouraging tax-free private trade outside the APMC mandis will make these notified markets unviable, which could lead to a reduction in government procurement itself. Farmers are also demanding that MSPs be made universal, within mandis and outside so that all buyers — government or private — will have to use these rates as a floor price below which sales cannot be made.

Will the new ‘freedom to trade’ Act benefit farmers?

- Resetting the way farm produce is traded within India, the Parliament on Sunday passed a set of bills that aims to liberalize agriculture markets. A new beginning—farmers will now have the freedom to sell their products to any buyer outside state-regulated wholesale markets and such transactions will not attract any taxes or fees.

- The new set of laws allows the direct purchase of produce from farmers outside state-regulated mandis (also known as Agricultural Produce Market Committees or APMCs) which have enjoyed a monopoly till now—and where trader cartels often manipulated wholesale prices to the disadvantage of farmers. Produce can now travel freely across states, and farmers, the government hopes, will receive a better price as trade opens up to the competition.

- After amendments to the decades-old Essential Commodities Act removed stock limits on traders and exporters, agri-businesses are expected to invest in post-harvest infrastructures like storage, transport and value chains.

Who gains and who loses from the farm Bills?

- Farmers have taken to the streets, protesting against three Bills on agriculture market reforms that were passed by Parliament

- In Punjab and Haryana, bandhs were observed, with blocked roads and mass rallies.

- Opposition parties and farmers groups across the political spectrum have expressed concern that the laws could corporatize agriculture, threaten the current mandi network and State revenues and dilute the system of government procurement at guaranteed prices.

Impact of farm bills on markets and farmers: Five indicators to track

- The government hopes competitive markets and higher private investments in the food supply chain will improve farm-gate prices. Here are five indicators to watch out to understand the near-term impact of these reforms.

- Firstly, freshly harvested Kharif crops will start arriving in the markets. The number to watch out for is to what extent arrivals in existing mandis drop. For instance, if arrivals drop significantly by saying, over 25% compared to last October (the peak arrival month), this would mean trade is shifting out of APMC yards to take advantage of the zero taxes and fees provision of the new regime. But without regulatory oversight and monitoring of transactions outside APMC mandis it remains unclear how the welfare impact on farmers will be quantified. If arrivals show no change year on year, that would mean a status quo for now.

- Secondly, data on wholesale prices have to be closely monitored to understand the immediate impact of the bills on farm gate prices. As crop production is expected to touch record highs following ample rains and higher plantings, a slide in wholesale prices could lead to unrest among farmers. More so, since the Prime Minister has assured that farmers won’t be denied procurement at minimum support prices (MSP). It is likely that farmers will hold the government accountable if prices drop and state procurement remains limited for pulses and oilseeds.

- The third indicator is how government procurement of food grains will change, especially in states like Punjab and Haryana. Will the Food Corporation of India use the services of commission agents and procure from mandis by paying over 8% in taxes? Or will the government procure from outside mandis while undertaking MSP operations? Any disruption to the usual procurement regime may lead to further unrest in these states.

- Fourthly, policymakers and the central bank may need to closely monitor how changes in the Essential Commodities Act will impact retail food inflation. With the government allowing private players to stock Agri commodities freely, chances of hoarding to manipulate retail prices cannot be ruled out. The government needs to closely track privately held stocks, else the current trend of high food inflation may not ease despite record harvests. A transparent regime on privately-held stocks is also required for trade policy decisions.

- Lastly, farmer groups need to closely monitor corporate interventions in agriculture markets. It is unlikely that private firms will immediately invest in value chains or set up private markets if state governments are not aligned to the reform agenda. A politically volatile situation will deter them from investing. However, it could well be the case that food companies use services of the much-vilified middlemen while procuring directly from farmers. But farmers are unlikely to benefit from such transactions.

Source: The Hindu, The Indian Express, PRS

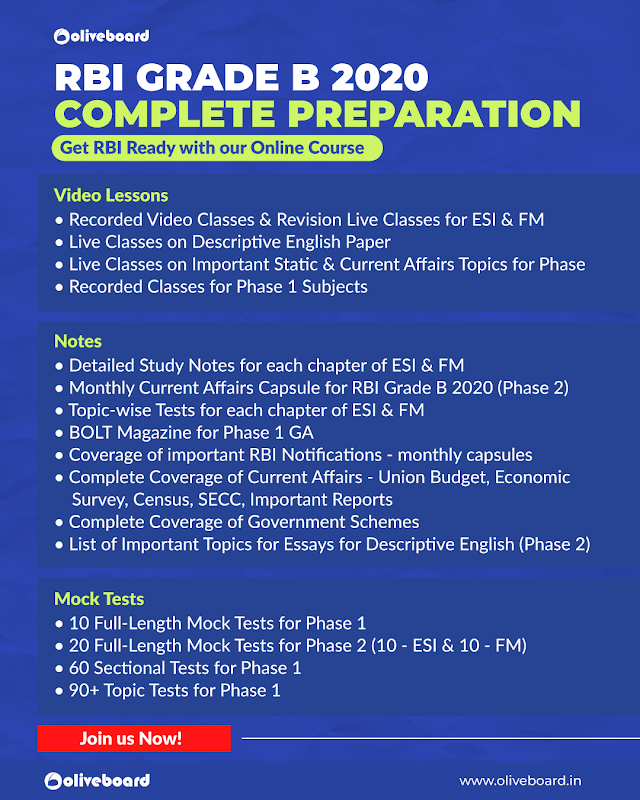

RBI Grade B 2020 Online Course

Oliveboard has come up with RBI Grade B Online Cracker Course for RBI Grade B 2020 Exam. Oliveboard’s RBI Grade B Online Course 2020 will be your one-stop destination for all your preparation needs

What all the course offers you:

Course Details

RBI Grade B Cracker is designed to cover the complete syllabus for the 3 most important subjects: GA for Phase 1 and ESI + F&M for Phase 2 exam. Not just that, it also includes Mock Tests & Live Strategy Sessions for English, Quant & Reasoning for Phase 1. The course aims to complete your preparation in time for the release of the official notification.

Features:

Use Coupon Code ‘MY20’ to avail a 20% discount on RBI Courses!

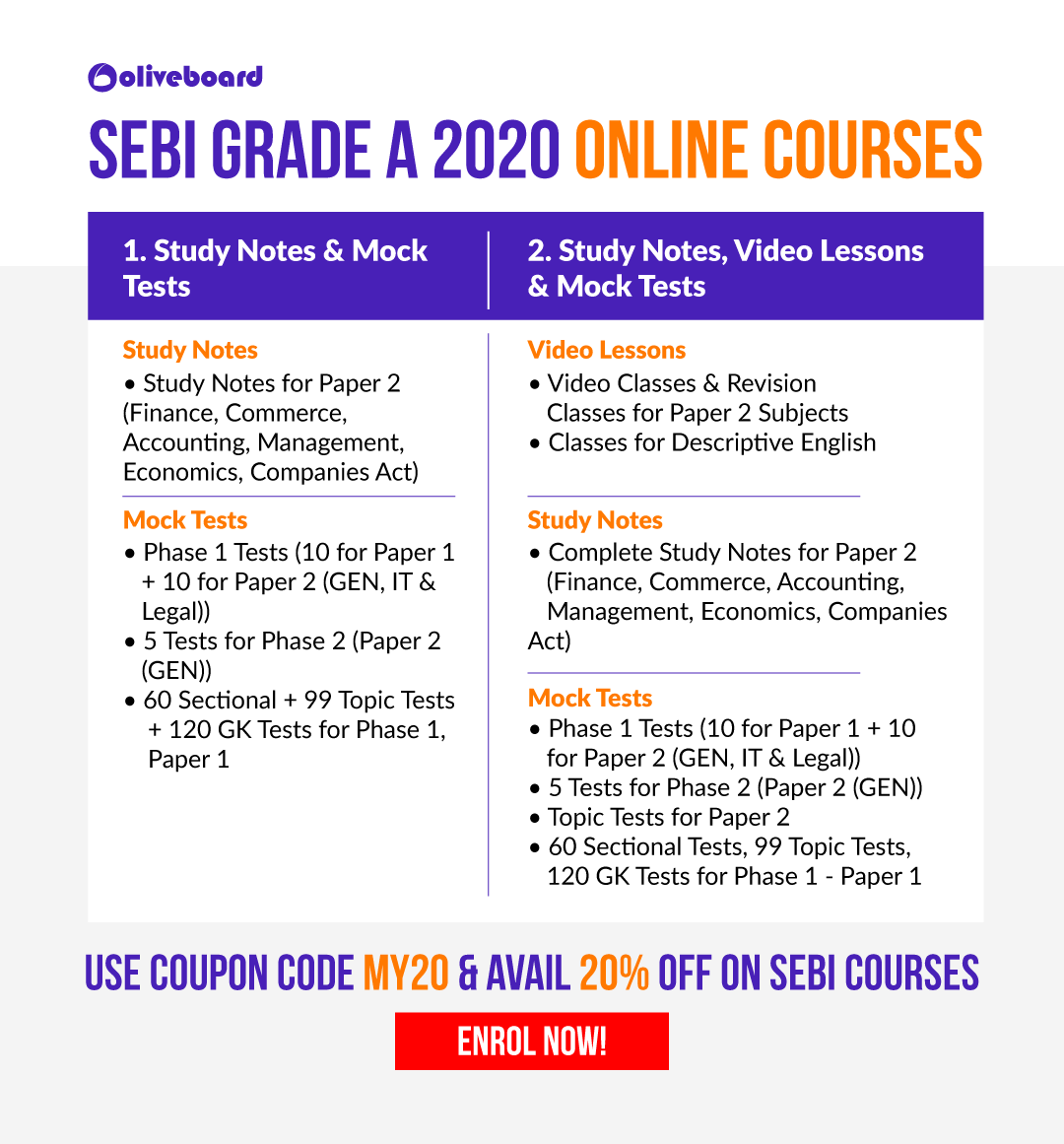

SEBI Grade A Online Course

For your Complete Phase 1 and Phase 2 Preparations

SEBI Grade A Cracker is a course designed to cover all the subjects under Phase I and Phase II exams.

- For Paper 1 of Phase I exam all essential subjects like Quantitative Aptitude, Reasoning, and English will be covered through video lectures.

- For Paper 2 of both Phase 1 and Phase 2, the complete syllabus will be covered through video lessons, and notes.

- The course will also have strategy sessions and past year paper discussions.

- This course has been designed in such a way that it can be covered well before the examination.

Enroll for SEBI Grade A 2020 Online Course Here

Course Features

Hello there! I’m a dedicated Government Job aspirant turned passionate writer & content marketer. My blogs are a one-stop destination for accurate and comprehensive information on exams like Regulatory Bodies, Banking, SSC, State PSCs, and more. I’m on a mission to provide you with all the details you need, conveniently in one place. When I’m not writing and marketing, you’ll find me happily experimenting in the kitchen, cooking up delightful treats. Join me on this journey of knowledge and flavors!